Context

Maintaining habitat connectivity is essential for species movements, resource flow, and ecological processes across landscapes. In aquatic environments, connectivity involves the continuous flow of water and linkage between water patches, crucial for enabling aquatic species to thrive and navigate the landscape. The Mekong River basin is home to diverse wetland habitats that play a crucial role in supporting biodiversity, providing habitat for various aquatic vertebrates, including the critically endangered Siamese crocodile, Irrawaddy dolphin, resident and migratory fish species, and several frog and turtle species. The ability of aquatic animals to move freely between feeding, breeding, and resting areas along sheltered waterways is crucial. The loss of both lateral and longitudinal connectivity stands out as a primary threat to the fish community in the Mekong River. Connectivity plays a pivotal role in sustaining viable fish populations, and preventing localized extinction in freshwater habitats is of utmost importance. The proposed NbS to address this problem aims at increasing connectivity through re-opening wetlands by removing dense patches of vegetation (native/invasive) that hinder fish movements and impede the free flow of water during the dry season, removing invasive plant species, such as water hyacinth, which can diminish dissolved oxygen levels in the water, often leading to fish kills and maintaining water quality to prevent chemical barriers, such as low dissolved oxygen and acid sulphate.

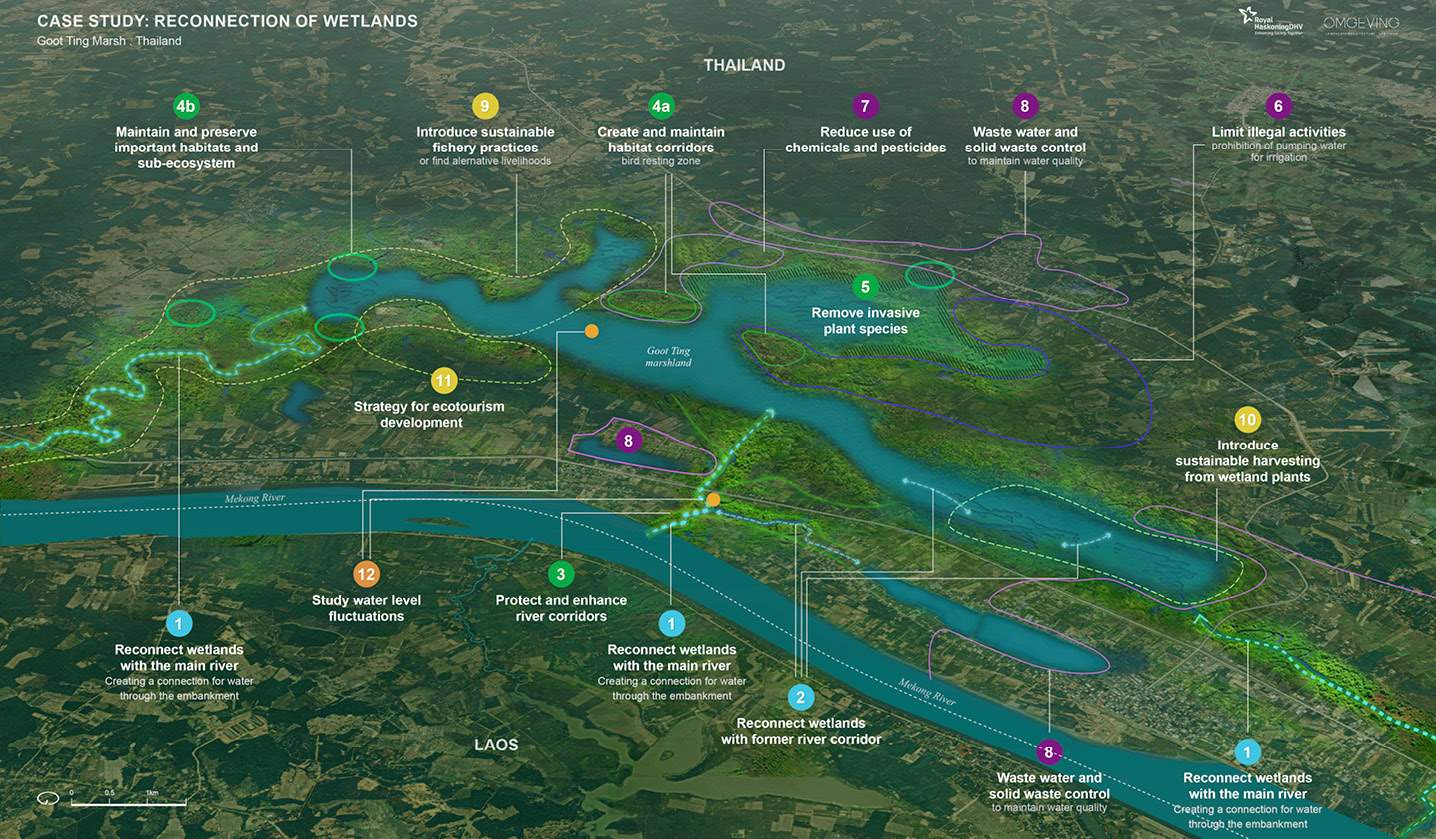

The case study area for NbS3 is the Goot Ting Marsh, which lies along the Mekong River in Nong Khai Province, Thailand, see Figure below. The site has high biodiversity yet faces a threat from hydropower dam development upstream. This development disrupts the natural river flow, exacerbating the drying of the marsh even after the rainy season. This alteration in the natural flood-drought cycle and sediment transport adversely impacts the ecosystem, posing a serious threat to fisheries productivity – a vital component of the livelihood for the surrounding communities. Approximately 23,000 villagers across 40 communities depend on the Goot Ting Marsh for their primary livelihood. By connecting the wetlands with the main river and establishing interconnectivity within the wetland area, protecting and enhancing river corridors, creating and maintaining habitat corridors, removing invasive species, improving water quality and introducing sustainable practices for the use of ecosystem services, the area could be restored and protected. Some data for the case study was provided by the WWF country office.

At the basin level, the area that is highly suitable for NbS3 is 880 km2. For the financial analysis, it is assumed that from the area with high suitability 25% will be part of the project area where riverine wetland ecosystems will be improved. This 25% is equivalent to 220 km2 or 23 wetland sites.

Figure. Case study area for improving riverine wetland ecosystems

Improving riverine wetland ecosystems and increasing the lateral and longitudinal connectivity with the main river would involve many stakeholders, including several government agencies. These stakeholders can be categorised into the following main groups:

Table. Stakeholders for flooded forest projects

Stakeholder group | Involvement |

Households | Directly affected by the project; beneficiaries of the project and are expected to diversify and shift their sources of income to more sustainable resource use |

Private sector companies | Potential beneficiaries of the project, adjusting to new or different business opportunities |

Government organisations | Design, implementation and support of the projects |

Funders | Provide loans, funds and other forms of financing for the project |

Society | At a larger scale, social, economic and environmental co-benefits will affect society |

In addition to these stakeholders, others can be identified, such as NGOs, knowledge institutions and contractors. However, these are not expected to be the main beneficiaries or responsible for the costs of the project and hence are not included in the financial and economic analysis. Note that there could be some overlap in stakeholder groups, e.g., government organisations could fund part of the projects.